In the ‘90s, I sewed myself a headband made of fleece. The material was in no way wind- or weather resistant and of course was also extremely air permeable. If you held part of it in front of your mouth and blew through it, you didn’t feel hardly any resistance to the airflow. Nevertheless, I sweat underneath good and proper while wearing it running. And I thought the whole story about breathability was a big fraud.

What does breathability mean?

In 2014, we did a field test for Gore in Scotland. Many of the participants were avid hikers and high-alpine trekkers. Some had the opinion that breathability was freedom of movement in your clothing. Others that it meant air permeability. And some others were convinced that breathability prevented sweating. The ideas these people expressed about breathability of their apparel was so utterly surprising and so diverse, that it was totally clear to me that nobody really understands what it is about. The term “breathability” is in itself misleading, but it’s become part of the vernacular used for performance apparel. Simply put: It describes how apparel allows water vapour to escape through the material to the outside.

Physics lesson: partial pressure difference and other stuff

If you really want the nitty-gritty: Water vapour is a gas. Gases of different compositions and concentrations tend toward commingling evenly. If for example the air in a room gets too stuffy, I open the window and air it out thoroughly. The stale air in the room mixes with the fresh air. That’s called partial pressure equalization potential. The concentration of stale air in the room is higher than outside, a so-called partial pressure gradient. Thus, the stale air pushes outward and the fresh air flows inward. If however there is an unpleasant smell outside, for example, if it’s time for the annual spreading of slurry manure in the fields, then airing out the room is useless. The same smells are outside as inside. But let’s get back to clothing: The body constantly gives off warmth and moisture, even at rest. Moisture and temperature rise between the body and apparel. Ambient moisture and temperature levels are typically lower as compared to the inside of the garment. Here, you have a partial pressure gradient between warmer, moister air inside and less moist, colder air outside. As a result, in its search for equilibrium, moisture moves through clothing to the exterior when you are active. This physics principle applies to every kind of apparel, with or without a membrane.

Breathability has its limits

Apparel in which I feel pleasantly comfortable while sitting, i.e. it’s neither too warm nor too cold, will quickly get too warm when I’m in motion. When I head out on a run, my body produces even more heat, and the body tries to get rid of this heat by sweating. Moisture comes from your sweat glands, is distributed across the surface of your skin, and then evaporates. This process of evaporation requires thermal energy, which is at the ready from the warmth of the body. As a result, your skin and body are cooled.

So what happens in apparel when you sweat?

If you get too warm, sweat penetrates your clothing. Plus, the sweat that has already turned into water vapour could then also recondense inside your clothing. No matter what I have on when running, I sweat and my clothing gets damp or even wet inside. Apparel that is considered breathable can’t stop that. It prevents neither sweating itself nor how clothing gets damp from too much warmth.

Then how does so-called “breathability” help?

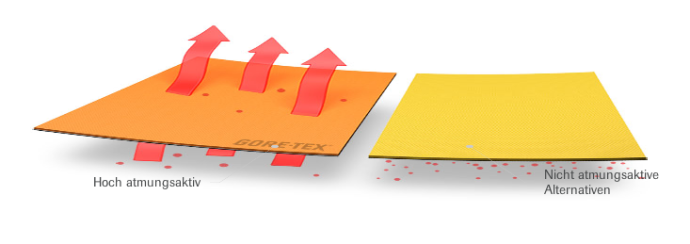

When I go for a run in the rain and put on a waterproof, breathable jacket with a membrane, then this jacket protects me from rain getting to me from the outside. Still, I get damp inside from sweating in the jacket. The bottom line here: Breathable apparel enables sweat to escape to the exterior. In contrast, apparel that isn’t breathable enough causes heat build-up.  In short... Membranes in functional apparel have a simple purpose: They keep out rain and snow, and moisture that comes from sweating can escape. That’s what makes apparel with membranes something special. It brings together two characteristics that were long thought to be total opposites.

In short... Membranes in functional apparel have a simple purpose: They keep out rain and snow, and moisture that comes from sweating can escape. That’s what makes apparel with membranes something special. It brings together two characteristics that were long thought to be total opposites.

Air permeable, but still windproof?

Some suppliers of functional fabrics demonstrate “breathability” by pumping air bubbles through a membrane that is fixed in an acrylic glas cylinder filled with water. That does show a certain amount of air permeability but no permeability of water vapour. Air permeability also enables the release of warmth, but not by vaporisation, rather by ventilation. If I’m in that stuffy room and want some powerful airing out, it goes more quickly if I can open two windows. Stale air is quickly carried outside and fresh air fills the room again. That’s precisely how it works with apparel. Certainly, a wool sweater keeps you warmer, but as soon as the wind blows, the warming layer of air next to your body is blown away. Air permeable membranes indeed do let in a little bit of air. These fabrics are however still windproof. In fact, the air permeability of these fabrics is so low, that you’d need a significant blast of wind to feel it.